Developable Clay

Published:

This project explores the intersection of developable surfaces and clay modeling.

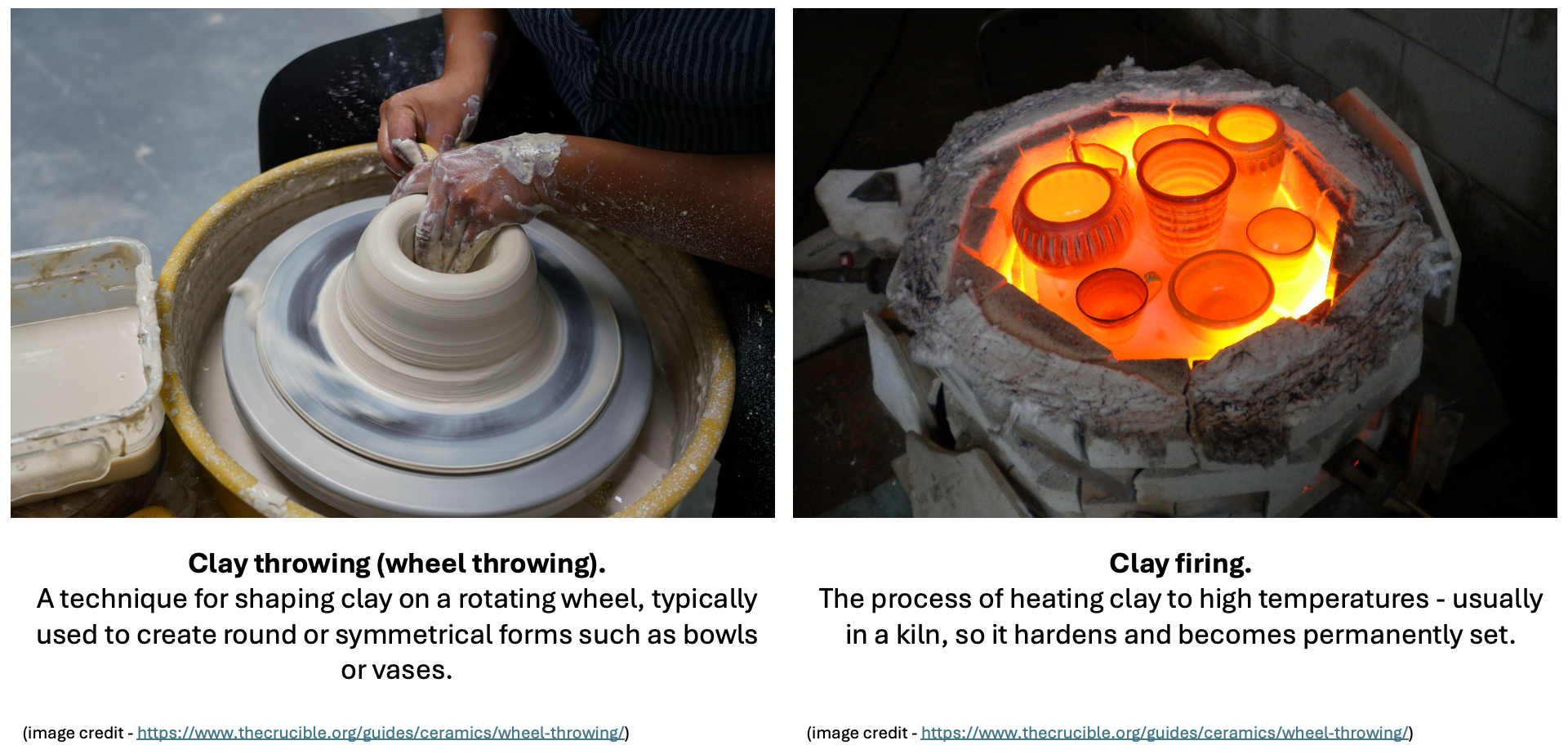

Clay modeling is my hobby; however, using actual clay is impossible at home. This is because clay requires: 1) firing at a high temperature (>1000 °C, 2200 °F) and 2) wheel throwing for some shapes.

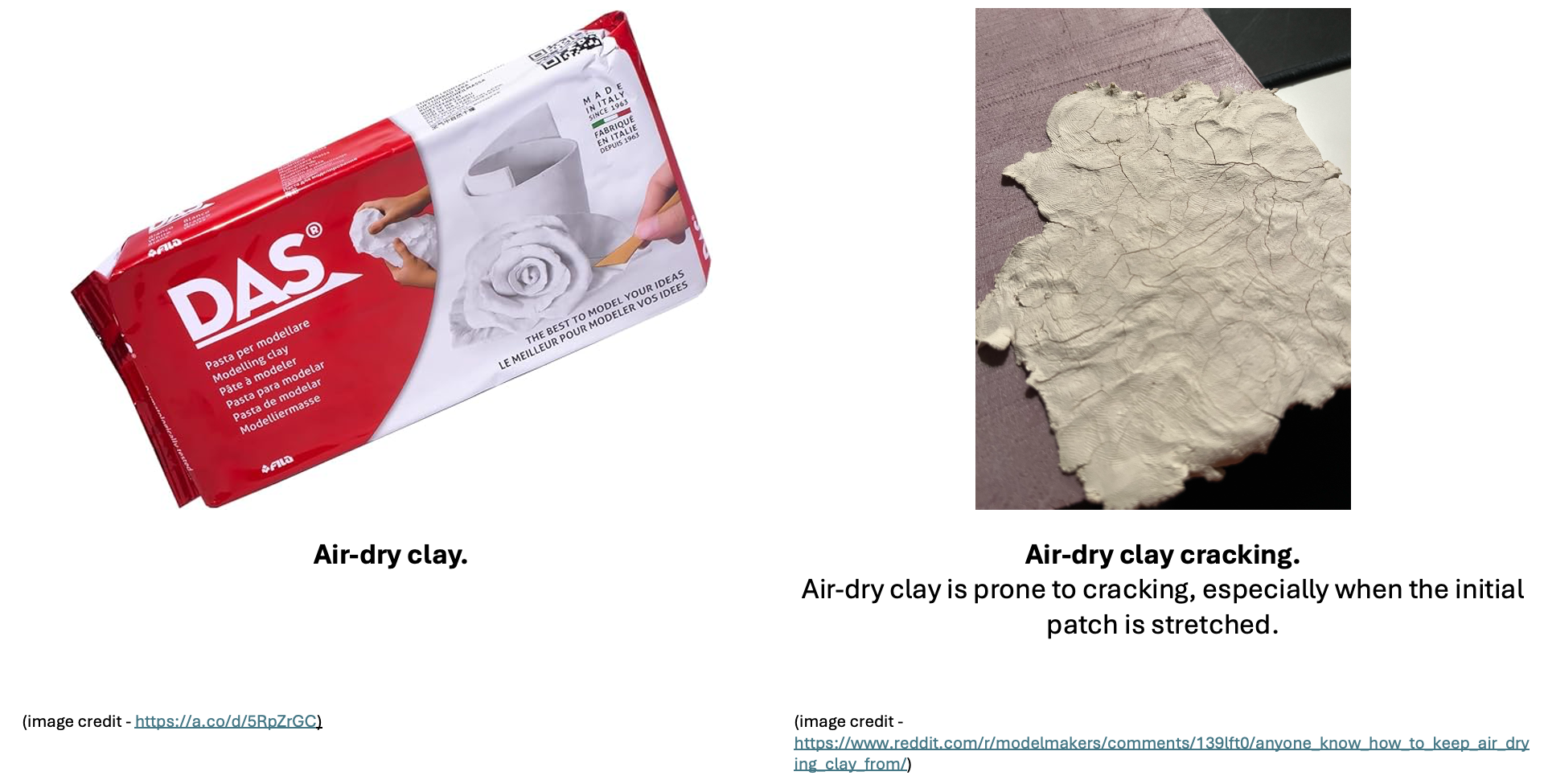

The best option for at-home clay modeling I have found is air-dry clay. This is a material that starts drying under air exposure, noticeably setting within a dozen minutes after you take it out of the package. It also has some quirks that are not commonly noticeable when working with actual clay. Most prominently, it is not that suitable for stretching, as it is prone to cracks.

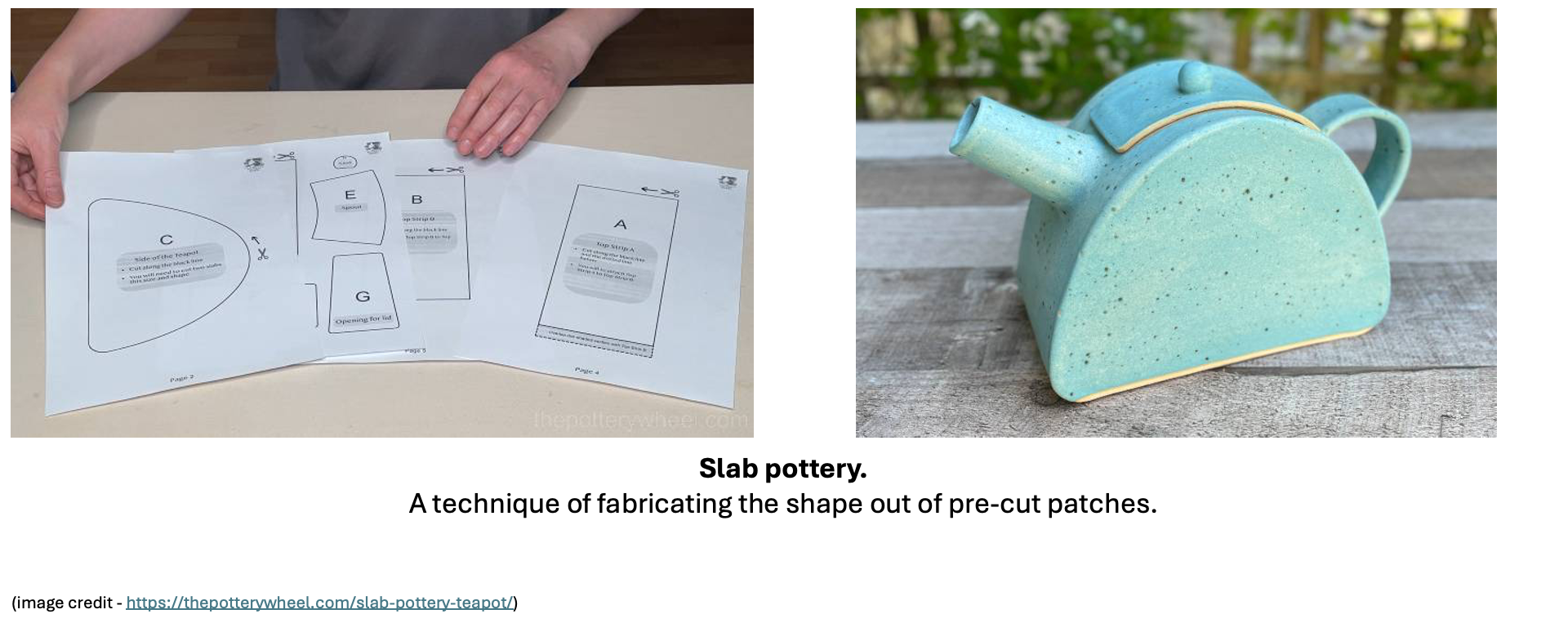

Hence, the most optimal solution for the shapes that are usually thrown with actual clay is to pre-cut and assemble patches. Apparently, this technique is known as slab pottery…

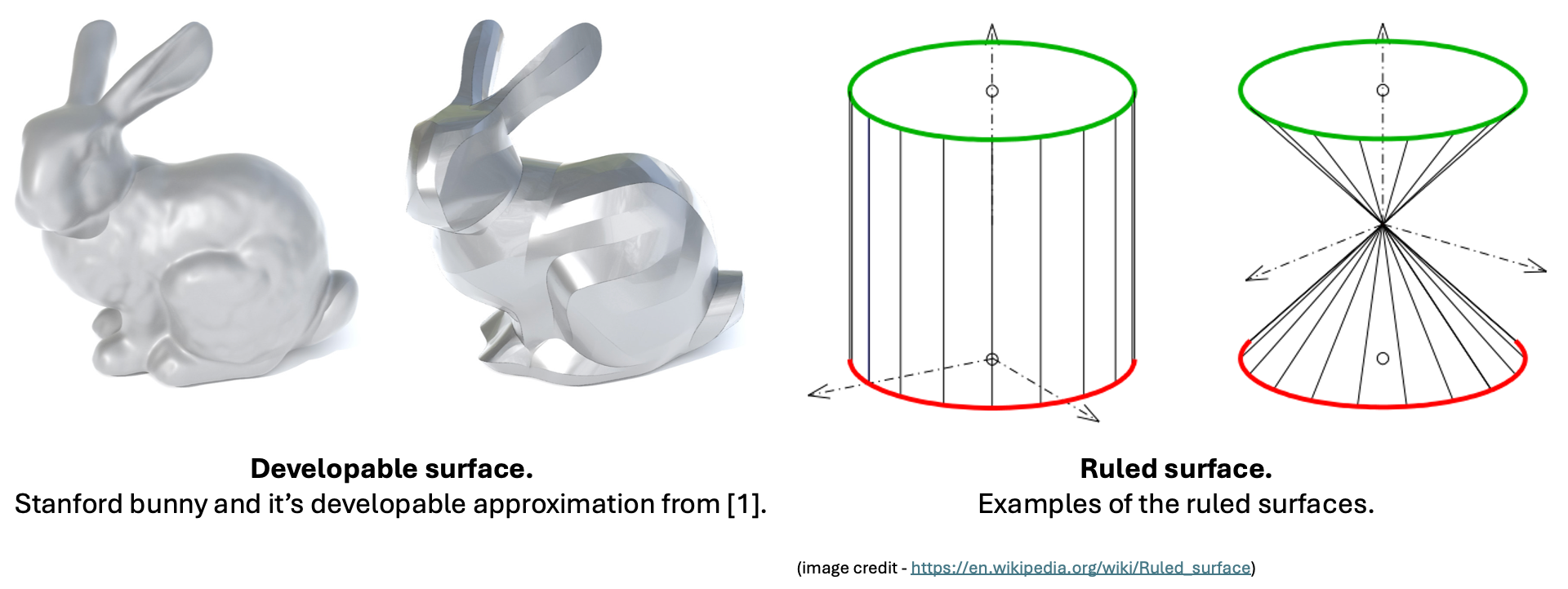

…which sounded like an interesting computational problem! If not solved computationally, it is tricky to know what patches to cut before fabricating an object, hence some automated estimate is needed. This led me to realize the connection to “Developability of Triangle Meshes” [1], which is a paper that studies the problem of developable surfaces.

A surface is considered developable if it has zero Gaussian curvature. As Gaussian curvature is just the product of principal curvatures, it means that one of the principal curvatures should be 0. Hence, we can imagine it as a surface that bends only in one direction. A nice property of such surfaces is that they can be assembled into the shape they represent with no stretching, only by bending — a key for fabrication.

Such surfaces can be constructed by sweeping a line segment, which results in what is known as a ruled surface. Every developable surface is ruled, but not vice versa. For example, a hyperbolic paraboloid (a “Pringle”) is ruled but not developable.

Upon investigating the results from [1], I realized that they do not facilitate human developability well. The outputs are dominated by a single large patch with very complex seams. Running their algorithm also requires quite a bit of hyperparameter tuning in my experience. I have also looked into the results from some other works [2, 3]; however, they are still problematic: 1) they feature quite complex seams, 2) patch position and orientation are not suitable for clay modeling, 3) they consider only single-shell surfaces. Their results are human-developable, but not out of clay that needs some time to harden.

The existing methods are also overkill for the shapes I wanted to fabricate. Hence, the requirements I set are:

- A simple method that can serve as an approximate guide to cutting the patches and assembling them. Approximation can be slightly coarser, because clay actually allows for a bit of stretching.

- Support for thickness embedded in the mesh. The vase mesh will have two surfaces on the interior and exterior sides of a single wall; the developable primitive I use should be able to account for that and represent it as a single patch.

- Facilitation of easy human developability, by following a natural ground-up fabrication flow that is suitable for clay modeling.

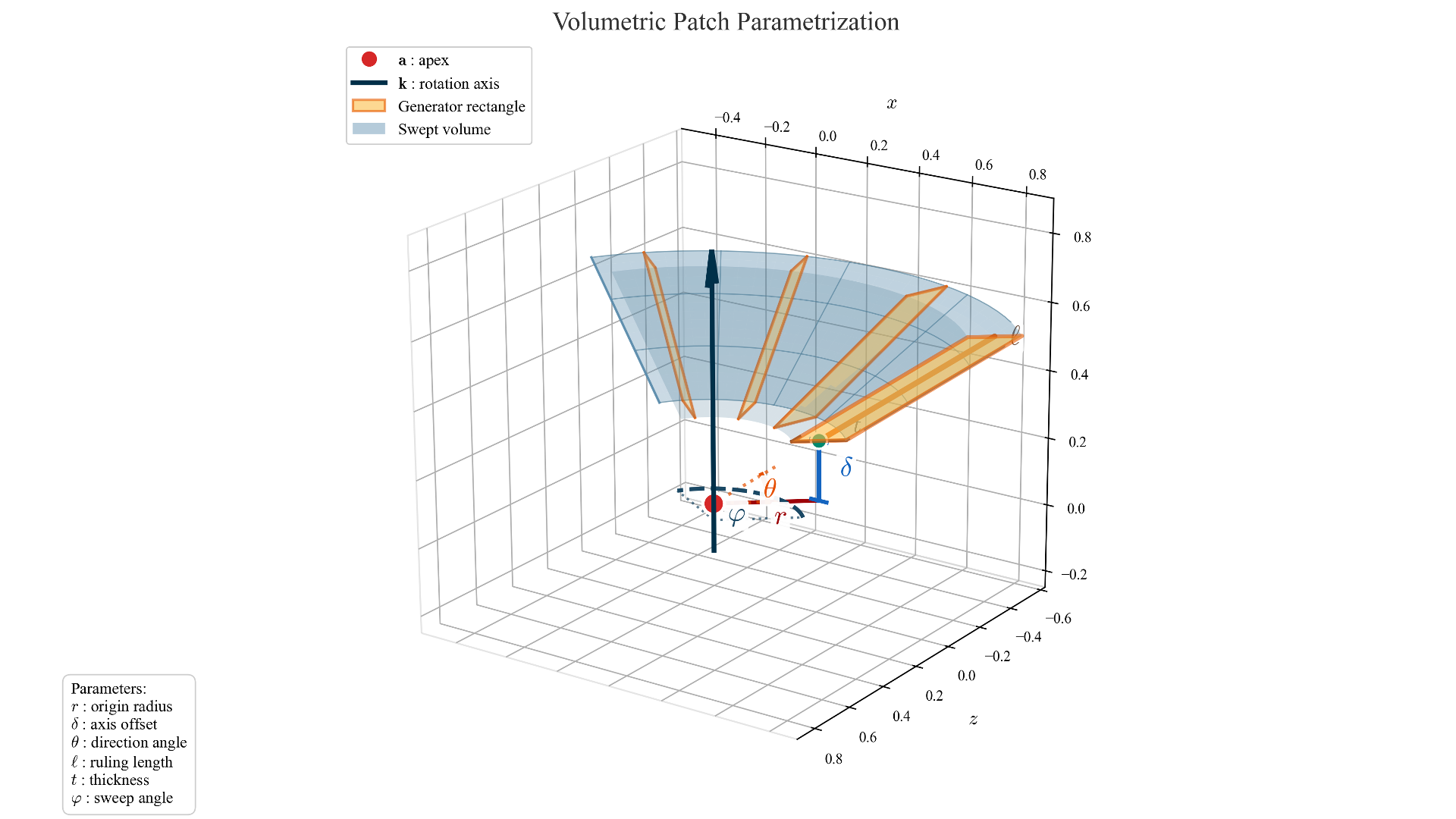

A family of primitives that is easy to work with can be parametrized as sweeping a line around some point, resulting in a conical, cylindrical or disk surface. This can be easily extended to a volumetric primitive, where instead of sweeping a line we sweep a rectangle around a point. The parameters defining such a volumetric patch can be used directly as optimization targets.

The method starts from initialization of patches. Initialization is done either heuristically or from some precomputed segmentation, depending on the shape complexity. The initialization is, unfortunately, very important for the method to work. Some of the strategies will be discussed in the examples further.

Next, the optimization begins. Points are sampled from the target surface; the patches are differentiably meshed and also get points sampled from them. The standard loss is Chamfer Distance (CD). However, I found that CD saturates easily; hence the values of the worst 5% of points are amplified.

In order to enforce patches to connect meaningfully, another loss leveraged is the loss connecting the top and bottom of neighboring patches. This is done simply by CD on the corresponding disk pairs.

Optimization is done with SGD for up to 2000 steps and a learning rate of 0.8. The first 400 steps are a warmup, where only the radius and thickness are optimized. Connectivity loss is enabled at step 800 and is weighted by 0.01.

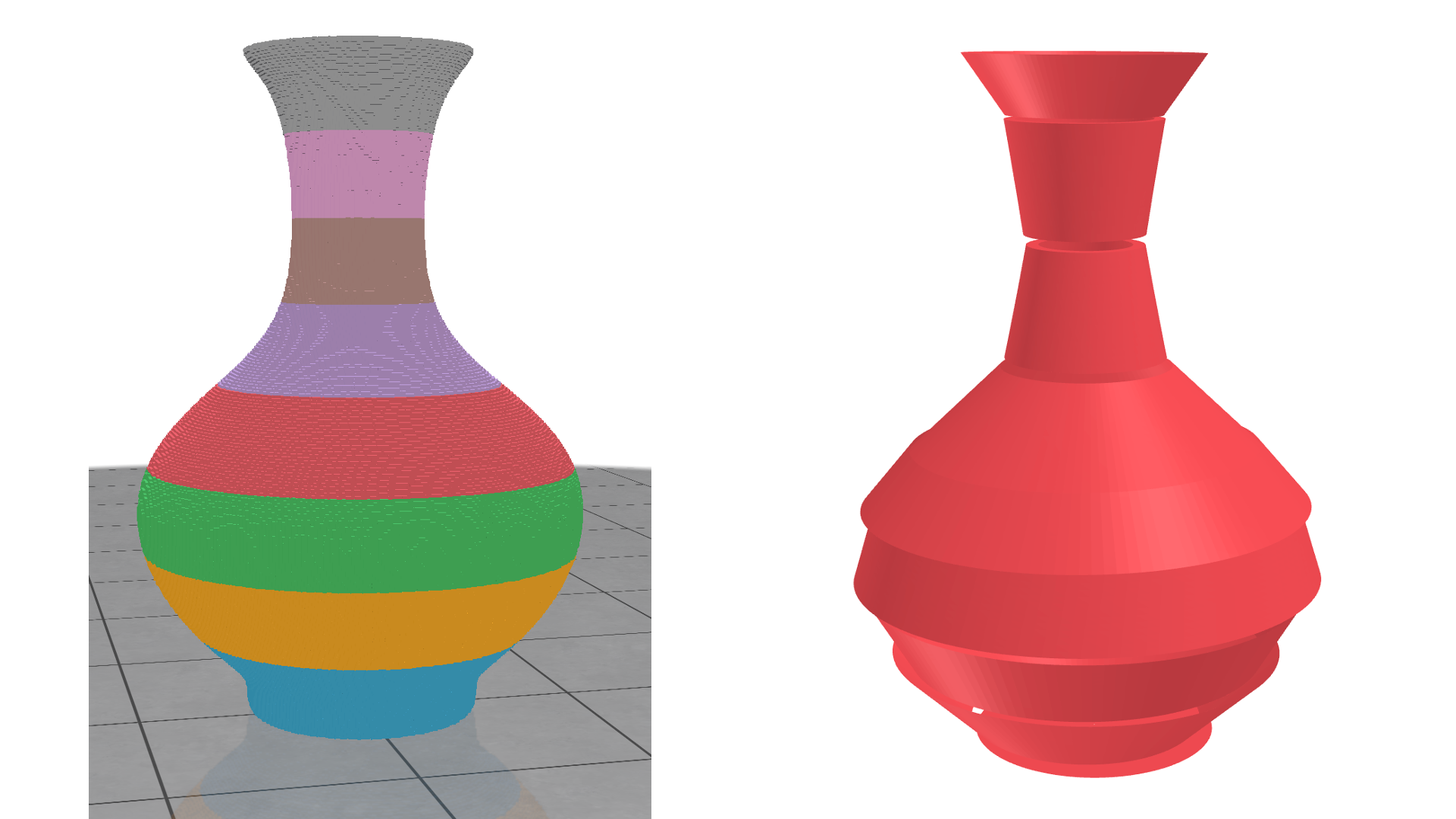

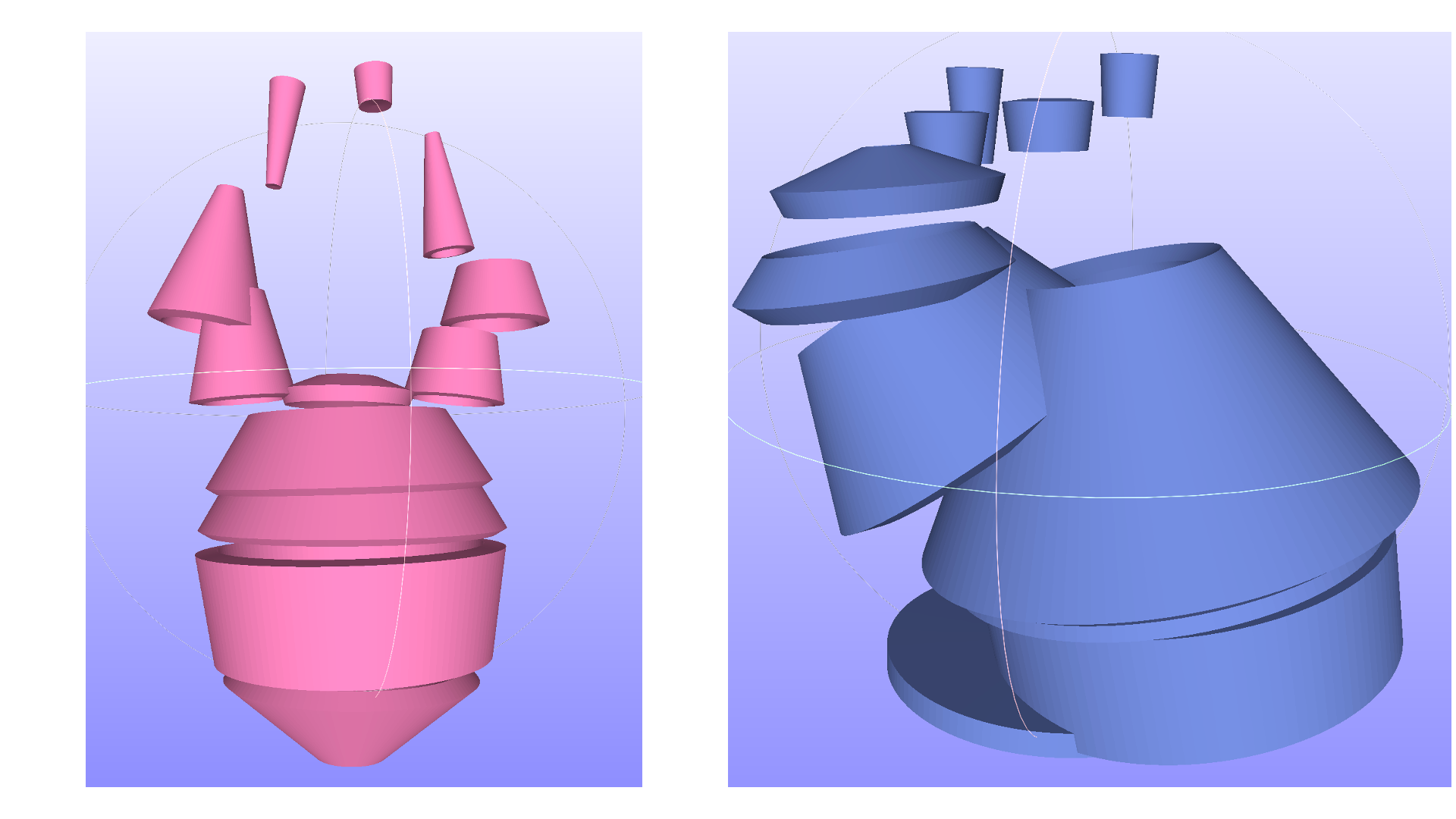

The figure showcases the initial segmentation of the vase on the left and the final optimization results on the right. As a part of initialization, we start by pre-fitting the primitives onto the segmented patches, followed by the global optimization described above. As you can see in the figure above, the resulting estimate of the shape is far from perfect. However, it is enough to achieve the goal of being useful to guide fabrication out of clay.

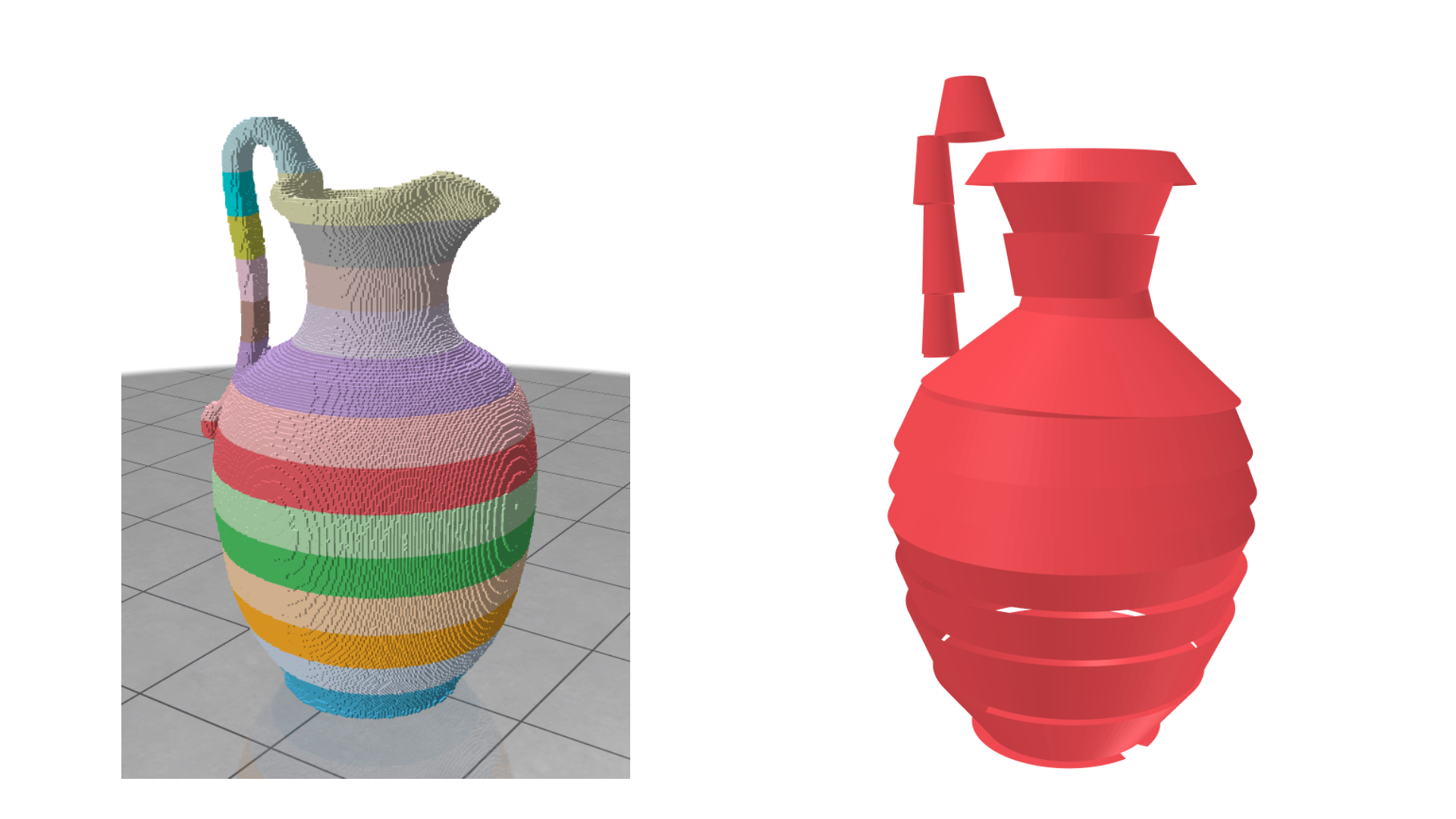

In this example, the shape is more complex due to the presence of a handle as well as more intricate geometry at the top. The handle is estimated fairly well; however, the geometry at the top is ignored and is approximated by a single patch. This is a limitation of both the initial segmentation and the parametrization.

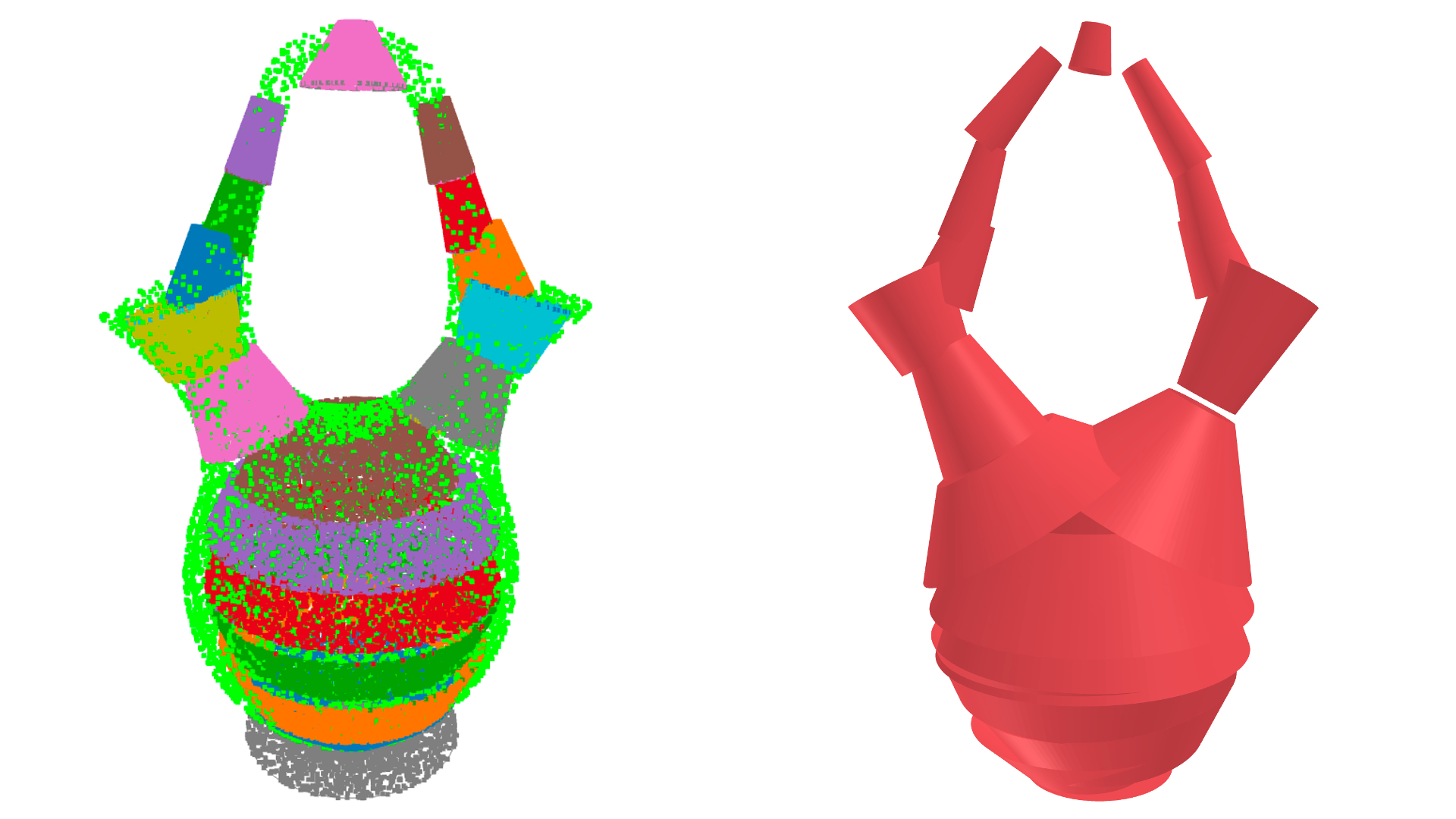

In this example, the image on the left shows the initial pre-fitting onto the segmentation. As you can see, during the optimization the structure of the shape changes quite significantly near the area where the handles are mounted. The patch arrangement also becomes asymmetrical. Though, once again, it is mostly good enough to guide manual fabrication.

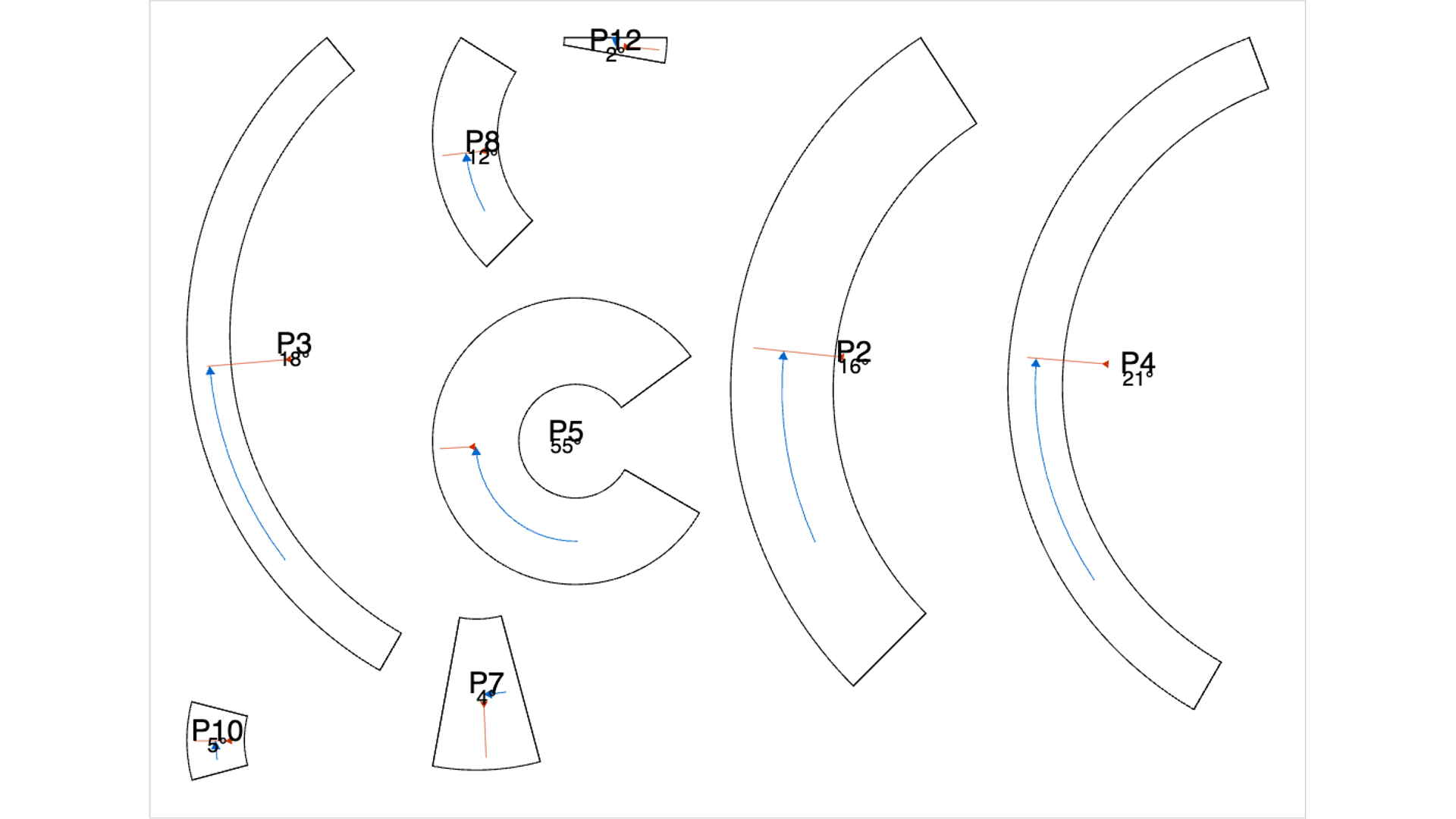

Finally, the patches are unwrapped into template pages so they can be printed out.

Now, I would like to discuss some strengths and weaknesses of the current approach.

Strengths:

- Given some simple tweaks, using extra clay and a bit of stretching, it achieves the goal of guiding fabrication out of clay.

- Using primitives instead of freeform patches facilitates simpler fabrication.

- Such primitives also provide some interesting and simple stylization options. For instance, I envision that there can be a collection of template stamps that, if selected, can be made into extra patches by copying the stamp along the length of the patch with some spacing. Then, such a decorative patch can be put onto the selected geometry patch. For instance, as in the example below but perhaps less intricate and easier to produce.

Weaknesses:

- The method is not suitable for automated fabrication and other materials, as the results feature many holes, misalignments and occasional regions of uncovered geometry. This happens due to multiple issues:

- The primitive I selected is constrained in what geometry it can represent. However, I believe that it can do the Stanford Bunny given some improvements.

- The optimization is prone to quickly falling into local minima.

- The connectivity of primitives is not guaranteed.

- Some of the patch parameters are basically “frozen”, which I believe happens because all the patches are being optimized separately and the interplay between them is weak.

- The performance depends heavily on the initialization. The current segmentation method is also insufficient for more complex shapes.

- The number of primitives stays static after initialization. Ideally, there would be some deletion/merging/splitting during optimization.

While I do not think that using this primitive family and, in general, the approach I selected is the ultimate solution for all shapes and more general developable surfaces, I do believe that using simple primitives for manual fabrication is beneficial.

Given the limitations discussed above, I will be exploring a slightly different approach further. I see falling into local minima and the “stiffness” of the optimization as some of the core issues. Hence, in order to facilitate information sharing between the parameters, I will be exploring an autodecoder approach next [4]. In this approach, we optimize a latent vector per primitive, as well as a shallow MLP followed by decoder heads that decode the primitive parameters. This approach is already showing some promising results but requires additional, careful loss design to enforce the nice properties we have (bottom-up modeling, etc.).

Alternatively (and likely better), this can be done by learning to deform a neural implicit function under the developability constraints.

Dec 14 update.

Autodecoder approach allows for simulatneous optimization of the per-patch latent vector and the decoder network that is used to obtain explicit patch parameters. Due to the nature of such parametrization being more coupled and continuous, it offers smoother optimization landscape.

As can be seen above, the vase results are better for the body but not the handles as compared to direct optimization results. At the same time, due to more flexible optimization and being less constrained by initial segmentation, such approach allows obtaining very coarse but meaningful results for the bunny.

The quality of the results yielded by the autodecoder approach is not consistently better than the direct optimization, mostly due to heavy reliance on the loss design. for instance, I found that lossese such as y-alignment (so that bottom-up developability is favored), and differentiable rendering losses are crucial for success of such an approach. Moreover, while being more flexible, it is still osmewhat constrained by the initial segmentation as it guides the optimization towards some local minima initially. However, removing it makes the patch placement too under-constrained. I envision that optimizing segmentation such that it follows the desirable constraints while being more flexible is the key direction for this type of the approach.

References:

[1] - Developability of Triangle Meshes. O. Stein, E. Grinspun, K. Crane. In ACM Transactions on Graphics, 2018.

[2] - Paper Craft Models from Meshes. I. Shatz, A. Tal, and G. Leifman. In Visual Computer, 2006.

[3] - Shape Approximation by Developable Wrapping. A. Ion, M. Rabinovich, P. Herholz, O. Sorkine-Hornung. In ACM Transactions on Graphics, 2020.

[4] - DeepSDF: Learning Continuous Signed Distance Functions for Shape Representation. J. J. Park, P. Florence, J. Straub, R. Newcombe, S. Lovegrove. In IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2019.